CONTEXTUAL IMPOSITION in CINEMATIC IMAGERY

Cover image designed for the blog post titled ‘Contextual Imposition in Cinematic Imagery.’

“When a painting is reproduced by a film camera it inevitably becomes material for the film-maker’s argument.”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

It may be argued that cinematic narration constitutes a form of imposition; for cinema, by its very nature, is an art form condemned to directly reflect an entire body of imagery. It achieves this by reversing the relationship between thought and experience that literature inherently possesses. From this, we must infer the following: cinema, in one sense, is an art that cannot escape classicism; for through the image—by directly transforming a thought that is destined to become an image—it becomes confined to the act of storytelling.

Book cover of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing.

However, when we claim that cinema possesses an inherently imposing mode of narration, this should not be understood as an imposition identical to that found in classical painting. Rather, it is an experiential and perceptual imposition. A film is not obliged to mirror reality; in fact, it often strives to move away from it. Especially in the era we live in, such a statement seems even more valid. As an art form that encompasses a vast spectrum of genres and cinematographic techniques, cinema does not necessarily aim to represent reality; yet it inevitably adopts an imposing attitude toward the viewer — precisely because it embodies the transformation of imagery into image.

Pages from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Pieter Brueghel’s Procession to Calvary and Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows illustrate the relationship between cinematic context and the reproduction of meaning through words.

What is addressed here is not a problem arising from the interpretive difference between the classical and the postmodern, but rather one that stems from the very nature of cinema itself. In a film, for instance, we are compelled to perceive an image from the very beginning. Then, through what that perceived image evokes in our senses, we construct a thought. It would be more accurate to describe this thought as the inscription of a feeling onto a sheet of paper. Yet the existence and sequence of the images we experience at the outset engulf us before we are even given the chance to escape them. Consequently, the formation of any subsequent thought remains impaired. In fact, this could be compared to a form of brainwashing; for what cinema does is to forcibly impose an image upon us and demand that we extract meaning from within it. Thus, as previously mentioned, this imposition does not originate from the classical mode of narration. The imposition in classical narrative lies in transmitting the image with all its realism, thereby relieving the viewer of interpretive responsibility. The kind of imposition at work here, however, is a contextual imposition upon perception.

In literature, this condition occurs in a manner that cannot be examined step by step — perhaps as the simultaneity of experience and thought. For instance, the detailed depiction of a character in a Balzac novel does not constitute an imposition in this sense, since the reader is not directly exposed to an image. Instead, a structure is gradually constructed through the mediation of words, and it inevitably varies depending on the individual reader. Suppose we bring together ten people who have read Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and ask each of them to describe Raskolnikov. We would then be confronted with the fact that every single one of them has formed a different image of Raskolnikov. Therefore, at the root of this issue does not lie a problem of classical narration.

Perhaps this is cinema’s greatest problem: it creates immediacy within communication. Of course, there are other art forms that appeal directly to the senses, such as music or painting; yet none can be as powerful as an immediate image. In both classical and rock music, for instance, certain formulas are employed to convey specific emotions. To express tension, closely pitched notes are used — as can be observed in the opening sequence of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). In Bernard Herrmann’s score, the friction of bowing strings striking adjacent notes produces a hiss that genuinely evokes a feeling of tension.

The same could be said for painting — particularly the most imposing kind, classical painting. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503) or The Last Supper (1495–1498) are often described as imposing works. But is the sense of tension in Herrmann’s music truly powerful enough to generate the same imagery of tension in every listener? Similarly, the image of Christ and his apostles gathered around a table in Da Vinci’s painting does not necessarily compel us to see it within a fixed context. Take, for example, Carpaccio’s The Ambassadors Return to the English Court (1495–1500): the depiction of ambassadors in a courtyard, the crowd, and the harbor in the background resemble a photograph. Yet this image does not impose a direct narrative context upon the viewer, since it is not a linear or sequential arrangement of images.

Cinema, however, operates differently. By presenting us with carefully selected film strips in a deliberate sequence, it introduces a direct contextual intervention into perception itself.

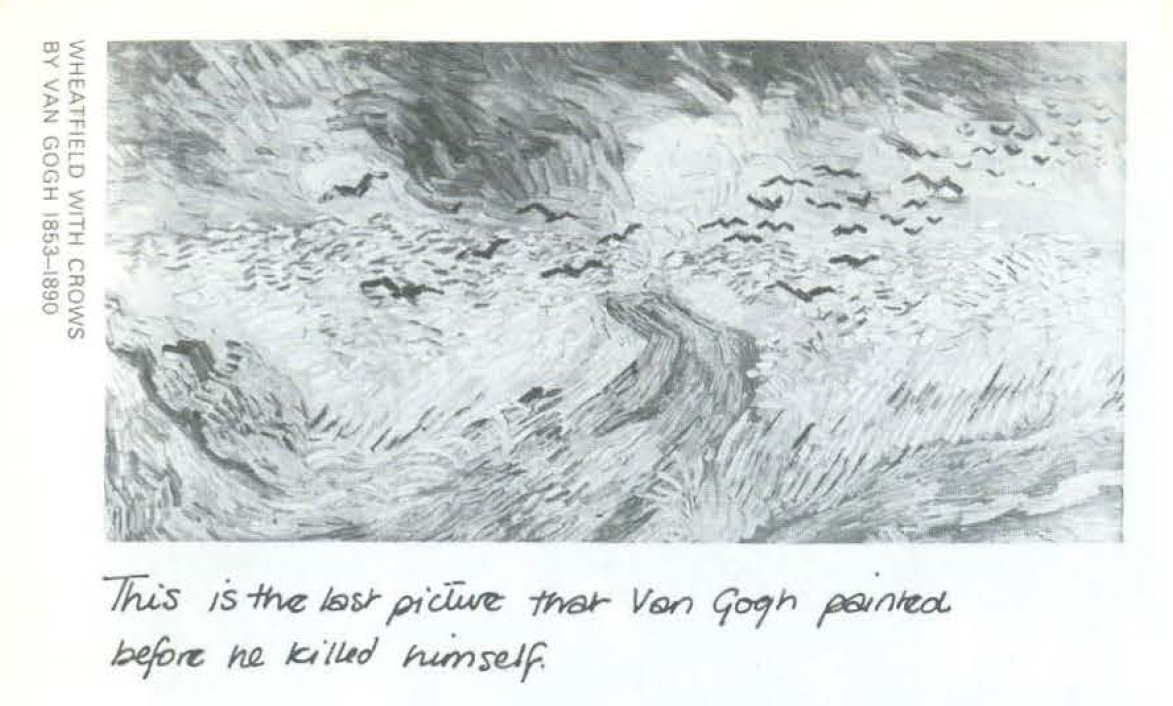

“This is the last picture that Van Gogh painted before he killed himself.”

John Berger points out a similar situation in his book Ways of Seeing. When one views the Van Gogh painting shown above—first with the caption beneath it, then without it—a distinction in meaning emerges, entirely dependent on context. The painting no longer conveys or evokes the same thing.

For this reason, it becomes necessary to demonstrate that even a film seemingly distant from reality cannot escape producing the same effect. Let us consider The Lord of the Rings (independently of the novel). In the film, the meaning of the ring is conveyed through a carefully constructed reflection of imagery that unfolds over hours of screen time, in order to embed the object within a coherent context. The purpose of this process is to communicate precisely what the ring signifies and why it exists. What occurs here, in fact, is the inscription of the ring’s entire functionality and existential reasoning into our minds through a sequence of images. Any further attempt to transcend this predetermined meaning will inevitably fail, for the image of the ring—framed within a fixed context—has already been directly imposed upon our perception.

But what if this were not the case? Suppose we encountered the same ring only in a photograph or an oil painting. In such a case, there would still be a direct intervention in perception; yet, as mentioned earlier, there would be no imposition of how that image must be read within a specific context. Nor could there be—for no artwork of such scale has ever been invented. In a painting or photograph, there is no flow of time; the narrative does not advance along a linear progression. Therefore, the image of a mystical ring within a painting cannot manipulate thought to the same degree that cinema can.

Ultimately, a filmmaker who is aware of cinema’s inherently imposing nature may be inclined to adopt a surrealist or impressionist mode of narration. Yet even such an approach remains, compared to similar expressions in other art forms, profoundly imposing. For instance, in David Lynch’s Eraserhead, the image of a premature—or perhaps aborted—infant is presented. If this image existed as a painting alone, we would not be obliged to interpret it within any specific context; we would even possess the freedom to transform it as we please. However, within the film’s linear structure and contextual framework, we are left with no such freedom. Therefore, even a surrealist film imposes a context upon the viewer, for it manipulates the human mind’s inherent tendency to establish connections between sequentially displayed images.

Similarly, one might argue that theatre operates in the same way; yet the principle of “here and now” liberates it from this predicament. Consider watching Beckett’s Waiting for Godot five times in a row at the theatre. In each performance, Estragon will never place his hat on his head in exactly the same way. If it were a film, however, the outcome would never change no matter how many times you watched it. Likewise, if we imagine The Lord of the Rings or Eraserhead as theatrical performances rather than films, both the ring in the former and the infant figure in the latter would be freed from the obligation of possessing the exact same imagery each time.

A kind of contextual imposition still exists, similar to that in cinema, yet in a theatrical production of The Lord of the Rings, numerous variables—such as the makeup of the orcs, Saruman’s gestures and expressions, and countless others—inevitably alter the context itself. In contrast, when it comes to The Lord of the Rings as a film, no matter how many times you watch it, the result remains unchanged. This phenomenon, in the end, perhaps makes cinema the art form that most constrains the power of thought and imagery.

“A film which reproduces images of a painting leads the spectator, through the painting, to the film-maker’s own conclusions. The painting lends authority to the film-maker. This is because a film unfolds in time and a painting does not.”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing